ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY

HISTORY, NEWS & POLITICS

HISTORY & POLITICAL HEADLINES

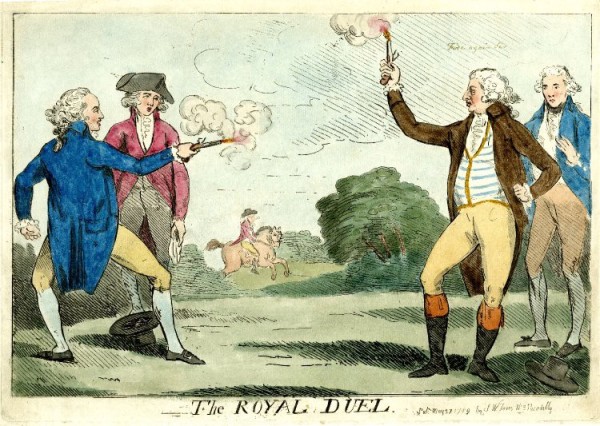

OTD in History… July 11–12, 1804, Aaron Burr kills founding father Alexander Hamilton in a duel

By Bonnie K. Goodman, BA, MLIS

On this day in history July 11, 1804, Vice President Aaron Burr kills founding father and political rival Alexander Hamilton in a sunrise duel in Weehawken, New Jersey, Hamilton would die the next day on July 12. The political rivalry was both political and personal, representing the worst in partisanship between the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. Historian Joanne B. Freeman called it in her article, “Dueling as Politics: Reinterpreting the Burr-Hamilton Duel,” “the most famous duel in American history.” The duel or “affair of honor,” also represented an extreme example of partisanship in the nation’s history. While the political rhetoric between Democrats and Republicans appears the most polarizing with the presidency of Donald Trump, in the era of the first emergence of the two-party system, political rivalries took on a more dangerous tone then a Twitterstorm with the soon fading art of the duel.

Hamilton was born in the West Indies, orphaned as an adolescent, and sent to the colonies for his education, later graduating from King’s College. Then he joined the Continental Army under General George Washington, eventually becoming his aid. Hamilton rose to prominence as a delegate at the Constitutional Convention, where he argued for a strong centralized federal government. Washington appointed him as the first Secretary of the Treasury and his monetary policy including the creation of the first national bank was essential to the new nation keeping economically afloat. In contrast, Burr was born to a rich New Jersey family, where he graduated the College of New Jersey, before entering the Continental Army, where he gained prominence during the attack on Quebec. After the Revolutionary War, Burr ran for New York’s State Assembly and in 1790 was appointed to the Senate.

Burr and Hamilton’s rivalry began in 1791, when Burr won a Senate seat away from Hamilton’s father-in-law Philip Schuyler, a Federalist. Hamilton kept exacting revenge on Burr. Hamilton’s attacks go back to 1796, when Burr ran for the Vice Presidency against Thomas Jefferson, claiming, “I feel it is a religious duty to oppose his career.” In 1800, when running mates Jefferson and Burr tied in the Electoral College, Hamilton swayed Federalist Congressman the House of Representatives to break the tie and back Jefferson with a blank vote as opposed to Burr, who wanted now wanted the presidency and refused to step aside.

In 1804, Aaron Burr was not renominated as Vice President on Jefferson’s ticket and decided to pursue the governorship of New York since Governor George Clinton, was chosen as the Democratic-Republican Vice Presidential nominee. Again Hamilton intervened, Federalists were divided between Alexander Hamilton supported candidate Morgan Lewis and Burr, Hamilton support for Lewis again lost Burr a nomination he coveted.

Hamilton’s intervention in the New York gubernatorial nomination and the subsequent correspondence with Burr led him down the path to a certain duel. On April 24, 1804, the Albany Register published a letter between Charles D. Cooper to Hamilton’s father-in-law Schuyler. The letter quoted some of Hamilton’s negative remarks about Burr. The letter read, “General Hamilton and Judge Kent have declared in substance that they looked upon Mr. Burr to be a dangerous man, and one who ought not be trusted with the reins of government.” Copper also said there is “a still more despicable opinion which General Hamilton has expressed of Mr. Burr.”

Burr responded to Hamilton in a letter “delivered by William P. Van Ness,” where he took most offense with the phrase “more despicable.” Burr wanted “a prompt and unqualified acknowledgment or denial of the use of any expression which would warrant the assertion of Dr. Cooper.” In a letter dated June 20, 1804, Hamilton refused to take responsibility for Cooper’s characterization, but he would “abide the consequences.” The next day, Burr responded, “political opposition can never absolve gentlemen from the necessity of a rigid adherence to the laws of honor and the rules of decorum.” Hamilton again responded on June 22, writing “no other answer to give than that which has already been given.”

Burr, however, did not receive the letter until June 25, Nathaniel Pendleton, who was to deliver it withheld it, while Pendleton and Van Ness conferred the following note:

“General Hamilton says he cannot imagine what Dr. Cooper may have alluded, unless it were to a conversation at Mr. Taylor’s, in Albany, last winter (at which he and General Hamilton were present). General Hamilton cannot recollect distinctly the particulars of that conversation, so as to undertake to repeat them, without running the risk of varying or omitting what might be deemed important circumstances. The expressions are entirely forgotten, and the specific ideas imperfectly remembered; but to the best of his recollection it consisted of comments on the political principles and views of Colonel Burr, and the results that might be expected from them in the event of his election as Governor, without reference to any particular instance of past conduct or private character.”

Burr’s final response was to challenge Hamilton to a duel, Hamilton, who had been involved in ten previous shotless duels, agreed. Most duels, were resolved peacefully before any shots are fired, however, Burr wanted his honor restored and Hamilton refused to recant his slanderous attacks against Burr. Burr felt needed to fight a gentleman and prominent politician as Hamilton to restore his reputation. Duels were illegal in both New York and New Jersey, but New Jersey was lenient and Weehawken across the Hudson was a popular ground for duels.

When the Burr and Hamilton met at 7 a.m. on July 11, there are conflicting recounts as to what occurred from Burr and Hamilton’s second’s Van Ness and Pendleton, respectively. The seconds had their backs facing the duelers both claim the shots were “within a few seconds of each other.” Hamilton chose his position as the one challenged, and supposedly fired a shot in the air above Burr’s head, shots to the ground ended duels; Hamilton sent a conflicting message to Burr. Burr responded shooting Hamilton in the abdomen near his hip, the bullet ricocheted and lodged in Hamilton’s spine, he collapsed immediately, and Burr was ushered away behind an umbrella.

Historian Joseph Ellis pieced together what might have happened in his book, Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation. Ellis believes both second’s versions of what occurred were motivated to spare either Hamilton’s honor or Burr’s future. Ellis writes, “Hamilton did fire his weapon intentionally, and he fired first. But he aimed to miss Burr, sending his ball into the tree above and behind Burr’s location. In so doing, he did not withhold his shot, but he did waste it, thereby honoring his pre-duel pledge. Meanwhile, Burr, who did not know about the pledge, did know that a projectile from Hamilton’s gun had whizzed past him and crashed into the tree to his rear. According to the principles of the code duello, Burr was perfectly justified in taking deadly aim at Hamilton and firing to kill.” (Ellis, 30) Historian Roger G. Kennedy concurs in his book Burr, Hamilton, and Jefferson: A Study in Character, writing, “Hamilton performed a series of deliberately provocative actions to ensure a lethal outcome. As they were taking their places, he asked that the proceedings stop, adjusted his spectacles, and slowly, repeatedly, sighted along his pistol to test his aim.” (Kennedy, 83)

Hamilton died the next afternoon at his physician’s home in New York. The outrage led to New York charging Burr for murder and dueling and his seconds for accessories to murder in August. In October, New Jersey charged Burr for murder as well. A number of Congressmen requested that New Jersey Governor Joseph Bloomfield have the charge dropped, which he did, New York eventually did the same. Burr was able to escape immediate prosecution because he was still the sitting Vice President, and he finished his term in Washington. Still, the court found Burr guilty of the misdemeanor dueling charge, which barred him from voting and holding political office for twenty years.

Despite their roles in the early founding of the nation, neither Burr nor Hamilton were honorable politically. After completing his term as Vice President, where he presided over Samuel Chase’s impeachment, Burr figured out another way to continue his political aspirations. In 1805, Burr with Commander-in-chief of the U.S. Army General James Wilkinson planned to take over part of the Louisiana Purchase territory, and form a new country with Burr as the leader, Burr also considered “seizing” some of Spanish America for his new empire. Burr put in his plans in motion in the fall of 1806, gathering “armed colonists” and going towards New Orleans. General Wilkinson fearing the ramifications, told on Burr to Jefferson. In February 1807, Jefferson had Burr arrested in Louisiana, and he was tried in Virginia for treason, however he was acquitted. The treason and dueling charges destroyed his political reputation.

Historian Thomas Fleming author of Duel: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and the Future of America does not have any more confidence that Hamilton would have been much better than Burr if he lived. In the CNN article entitled, “What if Aaron Burr had missed Alexander Hamilton?” Fleming described Hamilton as authoritarian leader who would have changed the course of American history and going against the Constitution, he was a part of creating. Fleming claimed Hamilton would have won the presidency in 1808, captured Canada in the War of 1812 creating the United States of North America. He would have broken apart the state of Virginia to smaller states, invade Spanish America to acquire Florida and Texas, and install a “puppet government” in Mexico. Hamilton would have industrialized America quickly, and abolish slavery.

Fleming noted, “The last letter Hamilton wrote before the duel called democracy a ‘disease’ that endangered the republic.” Hamilton would have “eliminated dissent,” instituted libel laws that would have “tamed newspapers” prevent them from ever criticizing is actions, and appointed every federal judge. Additionally, Hamilton would have created the “Christian Constitutional Society” making Christianity the official religion. Fleming notes, “At the 1787 Constitutional Convention, Hamilton had given a three-hour speech recommending a president should serve for life,” Hamilton would have put this theory into reality. Soon the Congress and Senate would have been filled with patrons and family members, making an “American royal family.”

Fleming concluded, “A handful of historians would begin debating an even more taboo topic. Astounding as President Hamilton’s achievements had been, they would begin asking each other whether it was a good thing that Aaron Burr had missed on July 11, 1804.” With the Presidency of Donald Trump journalists and historians find his behavior either unprecedented in American history or desperately try to compare to him to previous presidents, but many of his words and actions resemble Hamilton’s worst excesses; views of the journalists, presidency for life, and sabotaging and fights with opponents. For all the recent reverence for founding father Alexander Hamilton, President Trump represents what a President Hamilton might have been.

READ MORE

Ellis, Joseph J. Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

Fleming, Thomas. Duel: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr and the Future of America. New York: Basic Books, 1999.

Freeman, Joanne B. “Dueling as Politics: Reinterpreting the Burr-Hamilton Duel.” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 53, №2 (Apr., 1996), pp. 289–318.

Kennedy, Roger G. Burr, Hamilton, and Jefferson: A Study in Character. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Bonnie K. Goodman has a BA and MLIS from McGill University and has done graduate work in religion at Concordia University. She is a journalist, librarian, historian & editor, and a former Features Editor at the History News Network & reporter at Examiner.com where she covered politics, universities, religion and news. She has a dozen years experience in education & political journalism.